- Home

- Shira Nayman

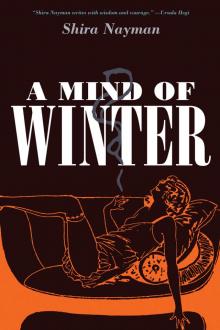

A Mind of Winter Page 2

A Mind of Winter Read online

Page 2

“Darling, why don’t we set up the pipe—” I said.

Barnaby’s hands glided upward under the front of my camisole. We slid to the floor. Barnaby’s robe fell open. With one hand, he unbuttoned my blouse, pausing over each one, the other hand still on my breast.

I attempted a small laugh. “The pipe,” I repeated softly.

Barnaby pulled away, looked at me appraisingly, then smiled. “Of course, my sweet, I’d forgotten your greed.”

He crossed to where his wet clothes were hanging on the coat rack and from an inner pocket, removed a small oilskin bag. Back beside me, he unfastened the pouch with what seemed like excruciating slowness—untying the leather thong, curling its ends into a loose knot.

“Where is the pipe?” Barnaby asked. I darted to the desk by the window and retrieved my small, cloisonné pipe. Outside, the sky held its cloud banks of sludge.

When I handed the pipe to Barnaby he placed his hand on the back of my neck and drew my face down to his. He pressed his lips over mine, and I had a peculiar sensation of collision, as if I were slamming up against steel. My efforts to mask my panic must have been successful for when we drew apart Barnaby still had a slow, dreamy face.

“I don’t know which appetite to satisfy first,” he said.

“The devil’s choice,” I said, forcing a smile. Waiting does this, I thought, looking at Barnaby through the pulsing red blurs at the corners of my eyes.

“It’s so wonderful, before we smoke,” he murmured.

Everything ached; where he nuzzled my breast it burned.

Time at a standstill. Gazing at Barnaby: frozen, distracted. For a moment I forgot him, I was thinking of somebody else. I was thinking of Robert. I’d heard he’d changed his name—how odd, that he would take on the name of his sad refugee friend from the Internment Center, Oskar, anglicizing it to Oscar. Of course, I can only think of him as Robert. Robert holding me, touching me, taking my spirit between his soothing palms. I closed my eyes. I might almost float there, I thought; I might almost float home.

“Here, Christine—” I opened my eyes. Not Robert, not home, but Barnaby, naked beneath his open robe, carefully handing me the pipe.

From the moment I set eyes on Archibald in the ship’s shabby dining room—which the crew, to their credit, had tried to spruce up with paper streamers and a few crystal pieces that had survived the war—I knew that Archibald and I would be friends. I drew a chair up to the crowded table, where Archibald was holding court among a group of fellow passengers, and soon found myself in the kind of lighthearted spirits I had not known since my university days.

Archibald was wily and clever, though never really serious, even when his talk turned lofty. This I knew from the inflamed joviality in his small, strangely pink eyes, and from the quizzical expression that never entirely abandoned his features. He was a strange fellow, at odds with himself, in a way that was stamped into his physical being. In contrast to the rest of his form—the thickened features of his face, whiskers like two gray scrubbing brushes at the sides of his jowls, the solid limbs arrayed awkwardly around his massive protruding center—Archibald’s hands were unaccountably beautiful. He must have known this for he kept them creamed and manicured and, on occasion, when mulling something over, would spread his fingers before him and regard them admiringly.

The mood on board was festive. Less than one short year since V-J Day, I found myself among people who, like myself, were eager to leave the drabness of wartime England behind. Archibald was the exception. He had only good things to say about his Beloved Motherland, as he called it. For reasons still unclear to me, Archibald had spent the war years in China. He had waited some months before booking his passage home. But, for all the expense and effort and anticipation of the journey, he had stayed in England a scant few weeks. “No point hanging about,” he said to me with a wink. “Just wanted to lay eyes on the Dear Lady, make sure she was still intact.”

The social life established on board continued uninterrupted once we were ashore. My first months in Shanghai were all parties and gay conversation. Archibald knew everybody—everybody who counted as far as expatriate society went. I soon discovered that my new friend had a deeper nature. We were sitting in the bar of the hotel where Archibald made his home, when he turned the conversation to his own early life.

“I’ve always known I had a calling,” he’d said. “Since I was a little boy. I wouldn’t have known what to name it but it was there, an irascible creature hanging around my neck wherever I went, wriggling and whining and giving me nasty little nips. Heavens, the days I spent wandering around Knightsbridge in a state. One thing frightened me: that the path, my North Star, when it finally revealed itself, would be unworthy—and please excuse the self-indulgence—of my largesse of spirit, of all the effort and duress.”

A tear bulged from the corner of Archibald’s eye. His self-pity seemed absurd, yet I could feel the prickle of tears myself—was aware of how I, too, as a child, had a similar desperate intimation of my own destiny.

“My severe trepidations were, alas, in the end, borne out,” he continued. “But by then, it was too late to alter my course.” Archibald fixed me with a disturbing stare, his pinkish eyes suddenly hard. “I say, how about an excursion? You must have heard about Han Shu’s café, on the Great Western Road. I’ve been meaning to take you there for some time. I have a feeling you and Han Shu will get along.”

I immediately liked the smokey, dim bar, with its cushioned chairs, polished wood beams, and well-attired clientele. Unlike other expatriate nightspots, Han Shu’s café—more of a nightclub, really—had held its own throughout the war. Rumor had it that after the Japanese occupiers had brutalized Han Shu’s friend, a Dutchman and fellow club owner, for refusing to comply with their extortionist demands, Han Shu had done what was necessary to secure his own safety and prosperity.

When Han Shu appeared, well into the evening, he turned out to be surprisingly tall, and of an unusual build: muscular and pudgy, both. His hair was a slick black cap, oiled and parted, razor sharp down the middle, and he emanated a potent scent—part floral, part musk. A single detail marred his otherwise meticulous grooming: when Han Shu smiled, which he did unself-consciously and often, his glossy lips revealed a stunted forest of richly stained teeth.

“A dear shipboard friend,” Archibald said, by way of introduction, nodding to me. Han Shu eyed me approvingly. “Meet Han Shu, a long-standing connoisseur of things British. And an important person in these parts.”

“A privilege, to meet such a beautiful woman. I am indeed most honored.”

Han Shu took my hand in dough-soft fingers and gave a low bow. I had not before encountered such a large Chinese man. As he lingered, half bent over, I studied the girth of his back and noticed him taking me in. There it was again, that almost palpable sense of thrill rising from a man, directed at me, which had long ago ceased to interest me. I wondered absently why physical beauty should occasion such worship.

Archibald looked first at me and then at Han Shu, and I fancied I saw in his face a paternalistic glow. His next words seemed addressed to himself.

“Yes. I’d like you to meet your spiritual guide.”

The rains scrubbed the city clean. Even the mosquitoes festering in the pools that gathered along the streets seemed like emissaries of goodwill.

I had not expected to find Barnaby in Han Shu’s smoking room—in the same building as the café but secreted from the bar at the end of a long corridor. So it was a surprise to see his square-jawed face appear above the rice-paper screen of the booth where I was sitting among a small group of customers. I stiffened and drew slightly away from my new acquaintance, a middle-aged specimen with mustard-colored hair and startled eyes.

“Why Barnaby, what a pleasant surprise! Meet Stephen—Stephen Stonehill,” I said awkwardly. Stonehill, smiling excitedly, seemed at a loss for words. “You will join us for a drink,” I added, aware of the anxiety in my voice. “We’re all going out

for a drive later, in Stonehill’s car.”

I smoothed the ripple of hair above my ear. Barnaby’s eyes followed the movement; their warmth felt like a caress.

“I have a quick errand to run,” I said quickly. “Why don’t you two get acquainted.”

I rose, lifting the hem of my dress, which I noticed was slightly frayed.

The corridor was almost completely dark; narrow glass shingles near the ceiling let in a greasy red glow. At the end of the hallway, by the front door, I recognized my contact, a thin Chinese man whose face was a plane of hard angles. Our business took barely a minute. Nodding curtly, the man left through the front door. He’d granted my request for an extension on the loan, but there was still the matter of finding fresh funds. I stood for a moment, alone, twisting my handkerchief in my hands, wondering how my savings, which had seemed so robust—surely enough to sustain me here for two years, possibly three—could have dwindled so rapidly. Archibald, I thought. He would help me figure out how to dig my way out of the mess I was in. I would visit him later at his hotel. Starting back down the corridor, I almost collided with Barnaby and hastily resumed my cheerful air.

“You will come with us, won’t you?” I said. “Stonehill’s a bit simple, but he’s awfully nice.”

“You’re in trouble, aren’t you,” Barnaby said.

“Don’t be a silly boy,” I replied brightly, linking my arm in his. “We’re going to have a wonderful evening. We’ll go to the American Bar and dance. I’ll take turns, though I can assure you that every moment I’m dancing with Red, I’ll be thinking of you.”

After a languid day spent with Barnaby, I readied myself for my nightly sortie to Han Shu’s café.

“Let’s give it a miss tonight,” Barnaby said. “I’m rather bored with the place.”

“You’re not going to give me reason to call you a stick-inthe-mud. You, of all people.”

Barnaby eyed me with uncharacteristic seriousness. “What do you see in a buffoon like Stonehill, anyway?”

I smiled. “Barnaby Harrington. I do believe you’re just the teensiest bit jealous.”

He smiled back. “Haven’t you heard? Life is painful, hard, and short.”

“Darling, that’s not how the saying goes,” I said.

“Well, I’ve got the short part right, and that’s my point. Life—time—it’s precious. Spend it with me. Don’t throw yourself away.”

He regretted his words immediately, I could see that; something in the air between us altered, like a sudden plunge in barometric pressure.

“There’s something else,” he said, unable to mask the darkness in his face.

“Yes?”

“You should stay away from Han Shu’s. It’s not good for you.”

I lit a cigarette, inhaled deeply, turned to face him.

“Barnaby, dear. You stick to your pleasures, I’ll stick to mine.”

Archibald was at his usual table in the hotel bar, his giant belly like a lost, friendly sea creature perched in his lap. Barnaby slung his panama onto the hat rack and sat opposite his friend in a cushioned chair.

“Out late again last night, I presume?” Archibald’s small eyes glistened beneath bushy brows. “Official business? Or intrigues of another kind? Nothing that a thick bristle from the dog that bit you won’t fix.”

Barnaby tapped down a cigarette on the side table. “Decidedly unofficial. And a decidedly fiendish dog.”

Barnaby enjoyed his little tête-à-têtes with Archibald.

“The usual suspects?” Archibald inquired.

“And a new chum of Christine’s.”

Archibald nodded glumly. “Christine was here earlier. We both know she’s a woman of broad gifts. As it happens, though, I’m a mite worried about her. She seems to be having trouble—how can I put it?—staying afloat. I’m afraid there’s some disappointment on the horizon.”

Barnaby drew on his cigarette.

Archibald craned his neck in search of the waiter. “Damn it,” he said good-naturedly. “Never there when you need them.”

“What do you mean—about Christine?” Barnaby asked.

“I’ve noticed a change in her. Not sure I can put my finger on it. I do believe the Romantics were right when it came to the charms of women. Innocence and grace. Call me old-fashioned, but it’s all in the manner. Unadorned coyness, that’s the measure of a woman’s regard for her own worth.”

Archibald stroked his belly with tender concentration.

Barnaby knew the man’s penchant for drama, and sensed that this was all a springboard for the real story he wished to tell. At last a waiter arrived with their drinks. Barnaby took a few slow sips.

“Which brings me to something I’ve been meaning to chew over with you, Barnaby—of a personal nature. If I may be permitted to prevail on your generous attention.”

Barnaby raised his drink in a toast, and Archibald continued.

“Imagine, if you will, a country under siege. Wartime. Shanghai cowers under the yoke of occupation. And there you are, as worried as the next fellow about your weekly ration of noodles, hoping you might have a few shavings of pork.

“You spend the morning on your toilette, making the best of the wafer of shaving soap left at the bottom of the dish. You rub only three drops of oil into your whiskers. You notice the dirt gathering in the head of your walking cane, in the creases of the lion’s mane. You didn’t ask for this war and you’re none too happy about it.

“You head down to the water, breathing in the smell of the quay. It smells human: sweaty, unclean. It smells like a brothel. This makes you hungry. Dirty children crowd around; the pier is rotting, you can almost hear the termites gnashing their teeth. The children have sores on their faces and feet. Some of the girls have babies tied to their backs with rags. They slip their filthy little hands into your pockets. You pat their heads and wonder if you should worry about lice jumping onto your fingers.

“The junks are bobbing up and down. You step onto the deck of the fifth junk from the end of the pier, balancing yourself with your cane. There are boys and girls inside the junk too, you know that. They’re older, old enough to know about life. Their mothers sit on crates, arguing about something.

“Now, Barnaby, here’s the question. Are you responsible for what happens next? Are you a person making a choice, or simply a cork in the current of history, caught in the timeless web of human misery? Oh dear, I’m mixing my metaphors. Let me put it another way. Are you, in the end, no more than an instrument of the human urge to destroy?”

Barnaby was aware of a creeping discomfort. He squinted through the smoke at his friend, whose face was the picture of affability.

“I’ve always thought that destruction was a form of creation,” Archibald went on. “Take a fire. I don’t mean a bonfire or a small kitchen blaze. I’m talking a real forest fire, an out-of-control devouring beast of a fire. Splendid, I say. Nature’s sylph. Alive. Even if what it’s alive with is its own end.”

He laughed roundly then leaned forward, earnest, his voice falling to a whisper. “Have you ever seen a house burn, my boy? All the way to the ground?”

Archibald finished his drink in a swift gulp, then glanced impatiently around the room. Sighting the waiter at the bar, he held up his empty glass, his face almost vibrating with anticipation. “And a little something to nibble, if you wouldn’t mind!”

He turned back to Barnaby. “Now, where was I? Oh yes, the junk. I know you’re a fellow after adventure; heaven knows the stories I’ve heard you tell about Africa. Now here’s an admission. Never have had a bit of ebony. But I’m awfully fond of the smooth jade you can collect out here—quite a bargain too—and the tigereye. Up north, if you look hard enough, a nice long sliver of hematite. They’re taller in the northern villages, you probably know that. Thinner too. Still tender, though, if you catch them at the right age. But a nice smooth onyx for my collection—did I say onyx? I meant ebony. Never mind, it’s all the same.”

The idea o

f Archibald being sinister struck Barnaby as absurd. Then why the feeling of alarm? Barnaby let out a quick laugh to mask what he was feeling, then tried to relax into the soothing languor afforded by the drink: was this his second, or already his third?

The waiter set down a plate, and Archibald greedily eyed its contents: a dozen or more small pastry shells, each containing a shrimp smothered in creamy sauce. Delicately, he picked one up between forefinger and thumb and popped it into his small red mouth, which was set like a shiny bright egg in the nest of his whiskers.

Outside, the skies were clear; a brief respite from the rains. As I waited for Barnaby—how many months had it been, these trysts with Barnaby?—I felt the familiar stirrings of disaffection. When Barnaby rounded the corner, and I saw the eager set of his face, my spirits dampened further.

As I opened the door, I could feel his ardor spilling into the room, sucking up the oxygen. I tried to return his smile, gripped by a desire to flee. Not Barnaby—I’d thought things would be different with him. The wine did nothing to quell the panic, so I reached for the bourbon, trying to distract myself from the fact that we had no opium to smoke.

“Darling, what is it?” Barnaby asked with genuine concern. Then, playfully: “You look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

I attempted to smooth the trouble from my face, puzzling over the tricks that feelings could play—little inner sprites that frolicked and squealed, then disappeared on a whim. I watched as Barnaby unpacked his satchel. He’d brought delicious morsels, as always, and whistled quietly as he set them out. Then, in a burst of cheer, he swept me into his arms and twirled me around. Around, around, the feel of his strength enfolding me, the room a sudden discombobulation.

“Barnaby,” I whispered, distress in my voice. “Put me down.”

He laughed. “Christine, you are wonderful.” His voice trembled with happiness.

He continued to spin me around; the room sped up. I threw back my head, fixed my eyes on the blur of the light, a sorry earthly comet, plummeting nowhere. No use, I thought, aware for a moment of a great, crashing sadness.

River

River A Mind of Winter

A Mind of Winter